It was never a peck on the cheek. Not once. Every kiss was a kiss, fully meant, and communicating. Well at least for me – and until it was yucky for my wife to kiss a woman like me. That’s why it has been so hard to live in a world without any kisses, that’s why my patient black dog, sitting beside me every day, feels she has something to wait for and remind me of. From several times a day to never, is tough. Woof!

I remember our last walk together in every detail. My memory is like that. It was along the river Cuckmere in East Sussex, and quite by chance it was a signposted walk: ‘The Kissing Gate Walk’. I think if I had been asked to find a final cruel irony, this would have been it, but it was accidental, and we had never been there before. Throughout our 32 years together, kissing gates on walks had always been just that: the gate you can’t allow the next person through until they have kissed you over the gate. And not one was a peck on the cheek.

But not this time. I realised with a real grief, that kissing gates are unlocked by sex, and for us, with penis-powered locks. And whilst I may in principle have had the key, it was not going to fit any more. I thought they were loving gates, but no, I was wrong. To kiss over a gate now, would have made my wife regard herself as lesbian, and for all the love we had known and shared for so long, that was such a complete turn-off, kissing gates were over for good.

Yesterday I went for a long walk and passed through a number of kissing gates, remembering several things, not just lost facility. I was recalling that going for a walk together was as two people who cared about and for each other, a companionship, a partnership, an intimate friendship. In fact, I had walked that way with other friends, and enjoyed it as much. And so, I have no doubt has and does my wife. She may fall in love again (I hope she does) and kiss her man over a gate again.

But when someone you have loved shows their gender identity, which has been there all along, to be unexpected, we come back to a theme of the early days of this blog: that when what you are depends on another, their change changes you. So to love me would make my lifelong partner a lesbian? And if by definition it would, what is the impact of that? That ‘I was never one of those, and cannot see or allow myself to be like that’? Do you really have to be different to love? How different is it really?

Love and sexuality: what is it that changes?

What is the psychological impact of someone you love apparently changing your sexuality? Does it? Is it about you? Or is it also that awful realisation that your ‘husband’ is a ‘lesbian’. What are they expecting?! Confusing or what! Is love seated in a gender that gives you your sexuality? Or is sexuality innate and fixed, so that you can only love providing the beloved complies with that self-perception? Why is it suddenly ‘yuk’ to kiss the person you’ve loved so long, not because they are suddenly physically different (they are not), but because that’s how they wish to be understood?

It’s all questions. I have some insight, because I have had to question my sexuality. I respond as a woman. I think I always have, but now, if a man treats me as a woman (say with flowers) I get the same warm feeling any woman would. Does that mean I had an innate homosexual latency? Am I now hetero for the first time? Where on the gender spectrum can I envisage greatest comfort in terms of a prospective kissing-gate relationship? To be honest I was surprised to have the feelings, but I feel very much more comfortable with the love of a woman. Not because I ‘was a man’ or because I conformed to that expectation and resented it (ie reject it) but because I want to be loved as a woman loves, not as a man does.

And so back to: ‘my husband expects me to be a lesbian?’ Or ‘What? My husband is a lesbian?’ (the concept of male lesbian is common in trans* circles). My wife felt that to allow me to remain intimate while growing into a new gender identity would make everything different.

Now for me to imagine kissing a man over a gate is something completely new. They would respond differently, maybe dismiss it as silly, or be a bit awkward or inept; maybe embarrassed and a bit ‘blokey’. It would be a very different and new experience; I would not know the response of this person, and would have to learn the interpretation of their gestures, the style of their kiss, the feelings behind the awkwardness, and of their own learning of me. Different, new, strange, learning from the beginning.

I never imagined that to continue making love in the same old way would be seen as so alien, just because I’d had hair removed from my chest and face. I never imagined that my touch, my loving, that everything I gave in intimacy with fingers, tongue, kisses, would become repulsive, shutting down all the familiar responses, because I was doing nothing different at all: only loving as I always had. But the perception of what it implied my wife should actually like was enormous: ‘I can love you doing that to me as a man, even with my eyes closed, but if you do the same thing to me as a woman, even with my eyes closed, it’s yukky.’ I can imagine a condition in which my body hair became naturally lost. She would not have rejected me. I can imagine untreatable impotence. She would not have rejected me. I can imagine a dreadful accident that damaged or severed my genitals. She would not have rejected me. Nothing emasculating would have led to the yuk factor. Because emasculation is not feminisation.

In living my true identity, the in-bred perception was that to continue to receive my love, and to let me into intimate spaces, she had to know that whatever might change about me, emasculating to every degree, I still identified as a man. Because to identify as a woman would require a change in her self-perception that was unacceptable. We often went through the argument: ‘What if it was me wanting to be a man?’ Of course I can’t answer that, because my whole view of gender is quite different (and I’m a woman!), but also for me, what – if she continued to be intimate in the same way, and to love me – would really be different?

Change and meaning

’The whole dynamic of a relationship and sexuality changes’, I was reminded. I accept this, but everything around us is changing all the time and we live by adaptation. If love is stronger than emasculation, why is it not stronger than feminisation? My question is why love has to change, and my answer was that if love is based always on the kind of attraction you began with in your teens, then your relationship is based more on sex than on love of the other. And I don’t actually want that any more; in fact I shall never accept it again. I want only to be loved as myself.

I have this image, that what I want most for my future in terms of relationships, is to find someone who wants to dance the dance of life with me. Someone committed by an idea of love that is about enabling the other, and with whom I can grow and learn.

I want love to dance. I want my kissing gates back.

And so we are back at kissing gates, and that awful last walk on a gorgeous sunny-blue-sky day. Kissing gates aren’t for kissing at all. They are to keep cows from straying into fields where they should not be; maybe it’s clover, or a crop, or just grass recovering. It is for their good. Do you like cows? You see a bunch of them all turning their heads towards you as you approach; do you feel threatened? These are all females, and what they do as their cycles rotate, is called ‘bulling’. They mock-mount each other. Does this make them lesbian? It comes naturally, and they have no scruples about it.

The irony was not lost on me, and I wrote this poem about it at the time, which sums up the whole thing quite nicely: Kissing gate. It’s about cows, lesbian identity, fear, and crap.

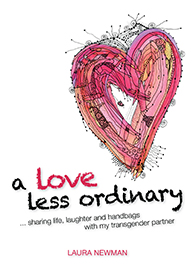

I turned up a scanned article someone helpfully sent me ages ago. It was about Helen Boyd and Betty in the early days. Great! There was Betty doing Helen’s make-up, and then Betty resting her head lovingly on Helen’s shoulder. This was a love less ordinary, surely?

I turned up a scanned article someone helpfully sent me ages ago. It was about Helen Boyd and Betty in the early days. Great! There was Betty doing Helen’s make-up, and then Betty resting her head lovingly on Helen’s shoulder. This was a love less ordinary, surely?