This week I turned up a scanned article someone helpfully sent me ages ago. It was about Helen Boyd and Betty in the early days. Great! There was Betty doing Helen’s make-up, and then Betty resting her head lovingly on Helen’s shoulder. This was a love less ordinary, surely?

I turned up a scanned article someone helpfully sent me ages ago. It was about Helen Boyd and Betty in the early days. Great! There was Betty doing Helen’s make-up, and then Betty resting her head lovingly on Helen’s shoulder. This was a love less ordinary, surely?

I was desperate, when I began to realise that my big unknown was gender dysphoria, to read, to buy books, to share the coming-to-understand. Desperate to show it wasn’t just me, in the hope that understanding would preserve the love in my partnership. I bought, as so many, My Husband Betty by Helen Boyd. We read it. It’s a great book.

The article has a pull-quote that says if Betty were ever to head for physical transition, their marriage would be over.

A trans friend asked if I had read the second book, She’s not the Man I Married. I wasn’t sure about doing that. It is in some ways the book of doubts. It’s the story of the uncertainty and impending change, it’s about love, identity and sexuality. One chapter is titled ‘Genitals are the least of it’. Phew! Could that be true? But it is about the period during which Betty had yet to commit to surgical reassignment (or correction). And the book ends still with all the fuzziness of not really knowing all that marriage and a trans partner implies, and whether Helen would still be the same Helen if Betty were ‘really’ to be just Betty. It was not a reassuring book to share, honest as it was.

Here was Helen full of doubts but full of love, accepting that her charming man she fell in love with was just an illusion.

My friend then said: ‘You know Betty has transitioned now?’ And if I remember rightly, I later read that Helen’s subsequent sentiment that has kept them together and campaigning, is that she just wanted still to be waking up with the person she has always loved most. But that isn’t in the book.

How many times did I say, usually in tears and fear: ‘You can walk away from this. I can’t!’? Hoping that the answer would be ‘I could never do that!’

There isn’t a third book, and we worked our way through personal stories, case studies of diverse lives, academic research. In fact most of the serious stuff you could get. It is all shot through with love, in the end, being the least of it, and why: that staying with a trans person erodes your own personality, identity, sexual certainty. That love is not – cannot be – enough.

There was nothing to say: ‘Hold on, this can work out. If this person [my trans partner] can go through so much, face such change, so much fear and pain, and retain self-identity, dignity and sense of self, stronger than ever – then maybe I can too.’

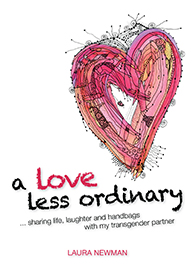

The new book: A Love Les Ordinary

Laura Newman’s book A Love Les Ordinary: sharing life, laughter and handbags with my transgender partner heads straight for this corner. It isn’t just the challenge of having – being known to have – a trans partner, it is that you can lose yourself in all the pressures and expectations of life anyway, and it is often the trans partner who shows the greatest honesty, strength and courage to be true to self. What if we were all able to do that? What if the issues aren’t about the trans partner, but about knowing that you are free to live life the way you should be, not just playing roles and meeting expectations? What makes a wonderful relationship? The sex you always thought correct? The ‘orientation’ you feel most fitting or comfortable with? No. It is one in which you know and love yourself with such honesty that you can be all you are with another who can do the same, regardless. Because then there is no compromise, no sell-out, no resentment that the other is preventing you being all you are. It doesn’t mean no give and take, it just means you both know it’s there and have agreed it freely. And it doesn’t mean no change, but that you can accept it together.

Maybe this harks back to something I wrote a long while back about other people not actually changing you, about honesty, and about how loving a person who never really was the ‘opposite’ but now shows it, doesn’t suddenly make you gay or lesbian.

The core of this understanding of love is that you cannot love another unless you love yourself, but that when you do, love matters more than any expectations.

You may have been told that already, through: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself’ (which is only a minimum requirement – you can end up hating yourself and therefore your neighbour!), or through the Buddhist tenet of lovingkindness needing you to love yourself first. But Laura demonstrates how this works out in a good relationship, how it makes a great relationship, and why being fully, honestly yourself is therefore a prerequisite.

There is surprise when I explain to others that, given the choice to have my lover and my family and my home back, with 40 more healthy years of life ahead, in exchange for living as a man – or to be the woman I am on medications that could endanger my life, and alone – that the latter is the only thing I could ever do. I can only love from who I am, loving myself as I am.

Laura’s book is not for trans people. It is mainly for women facing unconventional relationships, and the quandry of loving someone others would not respect you for. What does it do to you, and why does it do anything to you at all? Laura does address sexuality, but again, if you loosen your understanding of gender, perhaps you can just as easily adjust your understanding of what it means to love someone who looks more like you.

This book is not about accepting trans people or any special dispensation, it is about how two people can make a wonderful loving partnership through knowing themselves equally, so that they can give love unconditionally. There are amazing possibilities here, for any love relationship, and Laura’s earlier experience with an insecure transvestite left a significant foundation for starting a very different relationship. Helen Boyd also knew she was dating a cross-dresser from the start. I shall shortly review Emma Canton’s If You Really Loved Me properly too, so all three books of successful survival were neither taken by surprise after a long and happy marriage, nor unrelentingly heterosexual.

A Love Les Ordinary is a really valuable addition to the reading list for partners who have to come to terms with what it means to love someone who is transgendered. It does not go so far as to address the implications of a partner who is transsexual, but even there it is a good start. And it should be thrust into the hands of anyone who says they cannot understand how you could actually love, let alone be intimate with, someone transgendered.

I am still waiting for the book that says how a spouse can unconditionally love a partner who comes to terms with their gender rather late on, without losing their own sense of self. It is probably something to do with the realisation that they have happily loved a person not knowing that so much of what they appreciated came from something they would never have chosen. But I do know of a small number of marriages that have continued on the basis of ‘they are still the same person (not “man”) I married’.

When it is written, I hope still to be around to review it, because it would be such useful reading. Meanwhile, I am just longing for a love less ordinary.